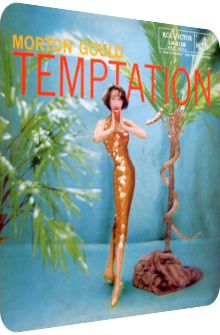

Morton Gould

Temptation

1957

Isn’t Cole Porter a genius? And can pizzicato strings evolve and leave their chintzy spirit behind? These questions are implicitly addressed by versatile composer and orchestrator Morton Gould (1913–1996) in the form of, right, an album. Temptation is that work of enlightenment, released in 1957 on RCA Victor, not coincidentally the very same year the Exotica genre got its languorous name and Gould came up with his oft-cited opus Jungle Drums (1957). I am quite a fan of Jungle Drums, but always disliked its most eminent flaw, the omission of any kind of exotic drum despite its cocky title. Temptation, on the other hand, does not inherit the legacy or premise and can therefore not be mocked or blamed for its inclusion of the bog-standard orchestra drums known as timpani. Whenever these drums occur, they add grandiloquence and oomph to a scenery of which there are 12 included. That being said, the variety of instruments is comparably large and chequered.

Gould throws everything into the tropical ring, from bolstered Space-Age strings over tramontane brass layers to woodwinds and mallet instruments. Harps, clarinets, glockenspiels and Flamenco guitars are happily united in most of the instrumentals, and Gould makes sure to prominently showcase the main melody on each composition. More often than not, the ensuing enchantment is dazzling and dizzying, with cavalcades of aural colors overflooding the synapses. This is one of Gould’s few highly accessible albums! 25% of its material derive from Cole Porter’s feather, with the remaining tunes being distilled from the book of Jazz standards. And heck, even two till three – back then soon-to-be – Exotica stompers find their way to Temptation. Things look good on paper… and are even better in aural form!

Temptation consequently launches with the title track, the best-known modus operandi of any label’s marketing buffs. Written in 1933 by Nacio Herb Brown for the glitzy movie Going Hollywood, it is arranged in a string-heavy way akin to – but not beating – Les Baxter’s version as presented on Caribbean Moonlight (1956). A clarinet (or trumpet, it is hard to say) is prominently embedded in-between the gently wafting glockenspiel-accentuated string washes. Brass sinews and bubbling double bass billows rev up the mystical-majestic aura later on. Pristine flute tones round off the climactic fanfare. Is this Exotica? The composition itself is often considered by quartets and orchestras alike, and I tend to verify this question in regard to Gould’s interpretation. It is clearly arranged in a poignantly classical way, no Latin percussion is embroidered, pompousness is all over this piece, and yet the gleaming horns and solemn strings spawn ruddish colors and dark shadows enough to make it an exotified take.

Up next is Consuelo Velázquez’s Bésame Mucho, another Latin gold standard regularly washed ashore on the isle of Exotica. The strings are longing and yearning as expected, but there are two particularly great interstices: firstly the desperado guitar which hides behind the coppice and becomes transparent when the thicket of textures is waning, and secondly the clinging tambourines which augment the percussion scale. Ashen musix box-like glockenspiels illumine the crepuscular noman’s land further, true, but all in all, Bésame Mucho is a dead-serious piece of devotion… with an interesting pool of textures.

The third track introduces Cole Porter to the roster, and his compositions prove to be important over the album’s course. Off we go with I Get A Kick Out Of You, a rarely considered Space-Age gem which shines and plinks in Gould’s hands. A pizzicato galore is united with ultimately euphonious brass-and-string concoctions. The listening subject seems to move joyously through the streets of, say, Paris, the scenery is bustling, magnanimously interspersed by an ecclesiastic and enchanting beatless magnification which allows a closer gaze onto aural landmarks. The dun-colored piano segue at its apex is out of touch, but soon enough, the mauve-tinted aurora is again established. This is one of those archetypical Halloween-compatible pieces. Think of Singing In The Rain with an interpolated magnitude of bliss and density. A superb inclusion, almost completely covered in light!

Whereas Kurt Weill’s and Ogden Nash’s Speak Low oscillates between serious overtones and mystically downwards spiraling star dust particles as envisioned by mallet instruments, and unites these tidbits with spiraling harps and pizzicato strings aplenty, Body And Soul by the quartet of writers Edward Heyman, Frank Eyton, Johnny Green and Robert Sour sports the physiognomy of a moonlit balcony where romance is all yours. How cute. Seriously though: the interplay between the strings and the diffuse vibes as well as the encore of the harp coils is enthralling and oddly enough not chintzy at all. Side A finishes with Cole Porter’s What Is This Thing Called Love? and sees the influence of the shady bass flutes decrease in favor of a sternly Latinized instrumentation. The strings are twirling frantically, the polyphonic horns emanate several sunsets at once, the droning timpani break the spine of every foe, and even afer repeated listening sessions, it is not clear what just happened.

Cole Porter here, Cole Porter there, pizzicato prowess everyhwere! Side B kicks off with a pointillistic four-minute take on Porter’s I’ve Got You Under My Skin. Besotted, aquiver with pleasure and strongly rapturous, Morton Gould replaces various spoilsport elements and goes all-in on magic, harmony and that Hollywood happy end feeling. Speaking of magic: Harold Arlen’s and Johnny Mercer’s That Old Black Magic is an equally convincing take, emitting the same colorful range of mirth and vivacity by focusing a tad more on the flute side. The best parts: the rising tension of the helical brass tones and the faint orchestra bells at the end.

While Ray Noble’s The Very Thought Of You offers more of the same – no offense or disappointment intended – by dropping lovestoned lachrymose string formations of saltatory emotions and comprising of those superb fugues in tandem with flutes and glockenspiels, Buddy Bernier’s and Nat Simon’s Exotica phantasm Poinciana is transfigured by Gould into a gorgeous, slightly pentatonic mirage of hyper-melodious string flumes, fir-green vibe globs and harp undercurrents. The melody is ever-beautiful and indestructible, but nonetheless superbly transformed into magic here. Gould’s downright best interpretation of the album, severely outshining Arthur Schwartz’s and Howard Dietz’s following tune You And The Night And The Music. This rather Latin take fathoms out the lamento side again, intensifying the stereotyped concepts of covetousness and caretaking once again before the Roman flourish of Cole Porter’s finale Night And Day is unchained in adjacency to orchestra bells, clarinets and dragonfly strings. Warmth and quasi-cosmic timbres are all over this magnificent Space-Age giant, the timpani lose their threatening complexion and rather underline the joyous turmoil. Morton Gould erects a monolithic closer, a stupefying orchestration of sumptuous greatness.

Temptation suffers from the same omission as usual, the exotic percussion is amiss, but the rest is absolutely stellar and should please every fan of symphonic Exotica works, and more so: this is Space-Age par excellence, for not only is the catchiness a given, the short sections of faux-enigmatic fragility and weirdness live up to the genre convention as well. The album will never reach the ominpresent status of Jungle Drums due to its less tropical title, but the selected material itself is beyond all blame. Be it the Exotica classics Poinciana, Bésame Mucho and the titular Temptation or the convivial Space-Age extravaganza in the shapes of Night And Day or the highly phantasmagoric What Is This Thing Called Love?, the album breathes euphony and exhales melodies. The bleaker and murkier arrangements such as You And The Night And The Music and said Bésame Mucho may seem like antagonistic ingredients in an otherwise saturated table of contents, but as I remind myself time and again, Exotica and Space-Age are not necessarily all about truly paradisal elations, especially not the Latin material whose dim-lit arcana are in fact the real deal and live up to the composer’s original vision, if not arrangement-wise, then at least in regard to the properly carved out melodies.

The addition of four Cole Porter songs does not match the roster of Gould’s Ernesto Lecuona-dedicated suite on Jungle Drums, but proves Porter’s stylistic variety and does not harm the flow of Temptation. Again, Morton Gould’s album will probably never gain the label of a cult classic, but a look at its front artwork and, more importantly so, the tracklist should both please and hopefully lure the Exotica fan who is willed to take a peak behind the genre-constituting quartet sound full of birdcalls. The album is available on vinyl and a remastered download version on iTunes, Amazon and cohorts.

Exotica Review 329: Morton Gould – Temptation (1957). Originally published on Apr. 5, 2014 at AmbientExotica.com.